Eating disorders are not a lifestyle choice, but a mental disorder that leads a person to eat in extremes. It can be too little food or too much.

Eating disorders affect not only a person’s mind, but their body as well, resulting in many possible health problems.

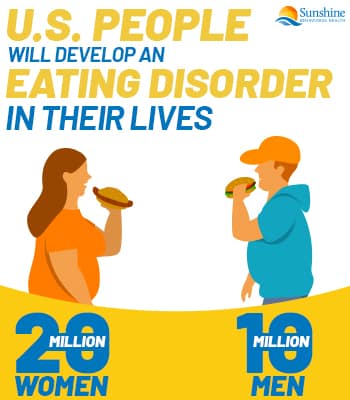

No one is immune to eating disorders. They can affect anyone, but they are more common among younger people and women in particular.

It’s not clear exactly what causes eating disorders, but a number of factors may contribute. Those include biological, psychological, and sociocultural elements.

Types of Eating Disorders

Types of Eating Disorders

There are a few types of eating disorders, but the most common ones are:

- Anorexia nervosa (anorexia), where a person deliberately eats very little, leading to extreme weight loss. Anorexics obsess about calories and may vomit (purge), exercise excessively, or use laxatives, water pills, or enemas.

- Bulimia nervosa will lead a person to binge eat. They’ll force themselves to purge after eating, or use enemas, laxatives, diuretics, or weight loss pills, starve themselves in between eating episodes, or exercise to excess to avoid weight gain.

- Binge eating disorder will lead a person to eat huge quantities of food, often alone, even when they’re not hungry. Afterward, they’ll feel guilty or upset. They may gain large quantities of weight. Some resort to laxatives, exercise, or vomiting to compensate for the huge caloric intake, but not regularly the way a bulimic individual will.

There are many symptoms that point to an eating disorder. An ongoing preoccupation with food, weight, and shape are three obvious signs. Over time people may struggle with concentration, become withdrawn, experience mood swings, and develop sleep problems.

Psychologically, a person with an eating disorder tends to be more vulnerable to mental health issues, including depression, anxiety, thoughts of self-harm, and low self-esteem. Substance use disorder struggles aren’t unheard of, either.

The specific symptoms, however, will vary somewhat depending on the disorder.

Anorexia Nervosa Symptoms

Even when extremely underweight, people with anorexia nervosa (anorexia) may view themselves as overweight. They may weigh themselves frequently, eat tiny amounts of food, exercise excessively, and purge or use substances such as laxatives or enemas to keep their weight down. They tend to

- Eat extremely little and infrequently.

- Become extremely thin.

- Obsess on achieving thinness.

- Be unwilling to maintain a healthy weight.

- Dread gaining weight.

- Have a distorted body image.

A person with anorexia may also dress in baggy clothes and layers. In part, it may be to hide their shrinking body, but it also can be due to feeling cold from extreme weight loss.

Anorexia Nervosa Complications

Over time a person with anorexia may develop a number of problems, including

- Osteoporosis (bone weakening) or osteopenia (loss of bone mass)

- Anemia, muscle wasting, weakness

- Dull, yellowing skin

- Brittle hair and nails

- Fine hair growing all over the body (lanugo)

- Constipation

- Low blood pressure and pulse

- Heart damage

- Brain damage

- Organ failure

- Feeling cold all the time

- Lethargy, tiredness

- Missed or stopped periods; infertility

Too few calories can cause the body to break down its own tissues for fuel. Muscles (including the heart) begin to break down. Blood pressure plummets. Risk of heart failure is all too possible. Without enough calories, a person may grow anemic or not produce enough white blood cells, which weakens the immune system.

Restricting food can lead to stomach pain, bloating, and nausea. It also starves the brain (which uses about one-fifth of the body’s caloric intake), resulting in low energy and reduced concentration.

Bulimia Nervosa Symptoms

Bulimia nervosa (bulimia) includes frequent episodes where people feel out of control as they eat large quantities of food. Then they compensate for that in some way, usually by forced vomiting, excessive exercise, fasting, or using laxatives or diuretics.

A person with bulimia can be underweight, average weight, or overweight.

Signs of a problem include

- Trips to the bathroom after eating (to purge)

- Packets of laxatives or diuretics

- The scent of breath mints or mouthwash to mask the smell of vomiting

- Hidden food stashes or empty food wrappers

- Scars or cuts on fingers (from inducing vomiting)

Bulimia Nervosa Complications

Self-induced vomiting and laxative use, in particular, can cause many problems, including

- An inflamed and sore throat

- Swelling in the neck and jaw areas

- Worn tooth enamel, sensitive and decaying teeth

- Acid reflux and other gastrointestinal issues

- Dehydration

- Intestinal troubles, constipation

- Electrolyte imbalances (too little sodium, calcium, potassium, etc.). This can lead to a stroke or heart attack.

Purging can also lead to pancreatitis (inflammation in the pancreas) or damage the esophagus.

Binge Eating Disorder Symptoms

Binge eating disorder (BED) is when a person has little control over their eating. Binging episodes are generally not followed by purging, fasting, or excess exercise. Many binge eating disorders individuals are overweight or obese. BED is the most common eating disorder in the United States.

Symptoms include:

- Eating huge quantities of food in a short amount of time

- Eating when not hungry

- Eating when full

- Eating quickly during episodes

- Eating until stuffed

- Eating alone to avoid embarrassment

- Feeling ashamed or distressed about eating

- Often dieting, but not always losing weight

Binge Eating Disorder Complications

Binge eating to excess can lead to weight gain and a number of related health problems such as:

- Diabetes

- High blood pressure

- High cholesterol

- A fatty liver

- Sleep apnea

In some cases a person may consume so much that their stomach can rupture. It’s rare among healthy people, but a person with out-of-control eating issues could be in danger.

There is also a condition known as diabulimia when a person with diabetes (usually type 1) restricts insulin in order to lose weight. Diabetes is also a high-risk factor for developing eating disorders.

Causes of Eating Disorders

There is no exact known cause of eating disorders. There are many risk factors, however, including biological, psychological, and social ones.

Genes may play a role in the development of an eating disorder, but something biological, such as an imbalance of brain chemicals, can contribute too. So can a close relative with an eating disorder or other mental health condition.

A person’s psychological and emotional health may fuel some issues too. Contributing health factors may include:

- Low self-esteem

- Perfectionist tendencies

- Rigid behavior patterns (feeling as if there’s one “right way” to do things)

- An impulsive nature

- Mood or anxiety disorders

- Body image dissatisfaction

- Problematic relationships

Socially, there are some situations that elevate the likelihood of developing an eating disorder:

Socially, there are some situations that elevate the likelihood of developing an eating disorder:

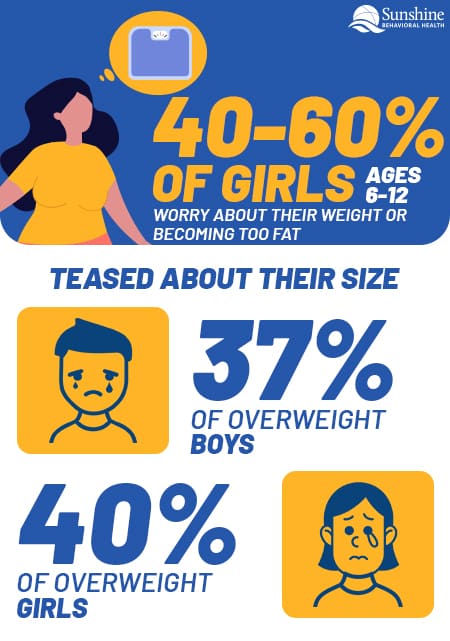

- Weight stigma, bias, or stereotyping

- Teasing or bullying

- Internalization of an “ideal” body type

- Sports or activities that focus on weight (gymnastics, dance)

- Loneliness, isolation, lack of support

- Acculturation (some racial and ethnic minority groups may be more vulnerable to pressure)

- Historical trauma (trauma that’s passed down from generation to generation, such as trauma from the Holocaust or a history of racism and slavery among African Americans)

Shared Risk Factors

Eating disorders share some common ground with substance use disorders. One study looked for characteristics between people with eating disorders and substance use disorders. They found several similarities:

- History of past abuse (physical and/or sexual)

- Stress or periods of change that trigger disorderly eating patterns

- Social peer pressure

- Dysfunctional upbringings

- Being impressionable to media and advertising messages

Many studies find an especially strong link between all forms of trauma and eating disorders, especially bulimia and binge eating.

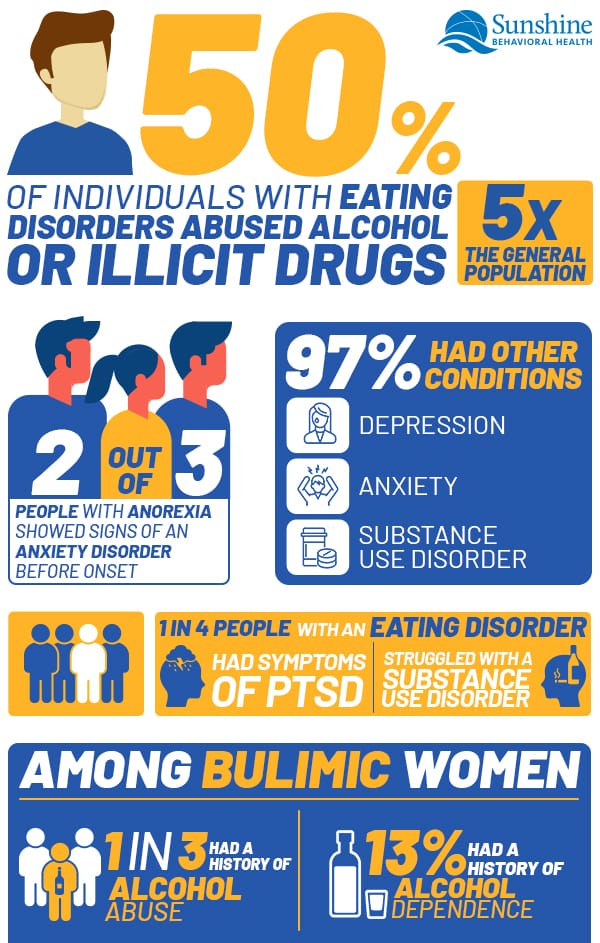

There are estimates that nearly half of all people with eating disorders have also abused alcohol or illicit drugs. About one in three individuals who have abused or were dependent on alcohol or drugs also had eating disorders. The takeaway: While one doesn’t guarantee the presence or development of the other, these disorders do co-occur often enough (and at a higher rate than compared to the general population) to merit a deeper look.

Abused substances include so-called diet aids such as emetics, laxatives, and diuretics (substances that induce vomiting, defecation, or urination, respectively) as well as illicit (or illicitly used) drugs such as alcohol, amphetamines, heroin, and cocaine.

Many of the risk factors associated with eating disorders — brain chemistry, genetics, family history, mental disorders, social pressures, and more — are also linked with substance use disorder.

Diagnosis of Eating Disorders

When diagnosing an eating disorder, a person’s symptoms (and sometimes their weight) are often the first hints of an issue.

When diagnosing an eating disorder, a person’s symptoms (and sometimes their weight) are often the first hints of an issue.

To confirm the presence of a condition, a person may undergo several exams to check their physical and mental health:

A doctor or clinician will check vitals. Lab tests will look for things such as nutritional deficiencies, liver problems, anemia, or thyroid levels being off, as well as any other health complications. (Such complications could include diabetes or sleep apnea in people with binge eating disorders.)

A psychological evaluation may be administered to learn if there are any co-occurring mental disorders. It will also look at attitudes about one’s body and weight.

A dietitian may quiz the person on their eating habits.

All that information will be used to make a diagnosis and shape a treatment plan.

Treatment of Eating Disorders

There’s no single specific way to treat an eating disorder. Because it includes addressing medical, psychological, and behavioral issues, the approach tends to be a team effort.

Exact treatments will be determined by the clients’ needs, but it’s usually a mix of nutrition education, psychotherapy, and medication. If a person’s life is in danger, they may be hospitalized.

Generally, treatment addresses the following:

Nutrition

The client (and sometimes the family, especially if the client is young) will learn about and be encouraged to develop healthier and more nourishing food choices. People with bulimia and binge eating conditions may develop tactics to avoid cravings.

Psychotherapy

Many approaches are available, but the main goal is to replace unhealthy habits with healthy ones.

One challenge is that some clients (people with anorexia, especially) may not want treatment. They may view their condition as a lifestyle choice instead of an illness.

Psychotherapy-based approaches to address eating disorders include:

- Family-based therapy. Here, the family learns to work together to develop healthier habits and better understand the issues facing the client.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). A form of talk therapy that can be especially helpful for bulimia and binge eating disorders. Clients work on monitoring and improving their eating habits and moods and build healthier problem-solving skills (learning to avoid triggers, etc.).

- Interpersonal psychotherapy. This approach can help people with bulimia and binge eating disorders by addressing relationship challenges and improving communication and problem-solving skills.

- Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT). DBT can treat binge eating disorders by helping people develop stress-handling mechanisms, emotional regulation, and healthy relationships (and boundaries) with others.

Medications

While not a cure, the right medication may help corral some urges and preoccupations.

Antidepressants may help with depression or anxiety, often associated with eating disorders.

Fluoxetine (Prozac) is the only antidepressant approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat bulimia. It can help even if the client isn’t depressed.

Vyvanse, more commonly prescribed for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), is the first drug approved by the FDA to treat binge eating disorder.

Other medications used for binge eating disorder treatment include topiramate. This medication controls seizures but can also help with binge eating episodes.

Treatment Goals

The goal for treating BED is to reduce the number of eating binges and develop healthy eating habits. May people with BEDs experience shame and poor self-image (and other emotions), so treatment may address those conditions. Depression may also be addressed.

Bulimia nervosa treatment goals include managing binge-purge cycles. That may include follow-ups with primary care providers, dietitians, and mental health professionals to help manage the issues before clients spiral into a full-blown relapse.

The first goal, especially for an anorexic, is to make sure their health isn’t in immediate danger, and to gain weight safely. If necessary, hospitalization may be required.

A huge challenge for eating disorders is avoiding relapse, since for many that’s a very real possibility that lurks in the background.

How Friends and Family Can Help

When a person has an eating disorder, friends and family can play a key role in getting them to seek treatment. Sometimes a person is unaware there is a problem, but others might be afraid or embarrassed to seek help.

When a loved one is struggling with an eating disorder, you may not be able to “fix” them but you can help. Here are suggestions:

- Learn about eating disorders and treatments; consulting a professional is a good idea

- Help the loved one recognize the problem; find a private place to talk

- Keep communication meaningful; be open and honest

- Use “I” statements like “I’m worried about you” as opposed to “you” ones like “You are too thin/fat”

- Stick to the facts

- Assure your loved one that their problem isn’t rare or shameful

- Find or develop a support network

- Be patient and a role model

- Take care of yourself

Some things to avoid when speaking to your loved one:

- Ultimatums; if not followed through, ultimatums can backfire

- Commenting on appearance or weight; those comments can say that size matters

- Mentioning what they’re eating (or not eating); that can make them defensive

- Shaming and blaming

- Overly simplified solutions; eating disorders are too complex for “Just eat more/less” statements

- Self-blame

Finding Help

There is plenty of information available to help people who are struggling with an eating disorder or who are concerned about a loved one’s eating disorder.

- National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA). The nonprofit offers screening tools, a helpline, a database of treatment providers, and other information.

- National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorder(s) (ANAD) is a nonprofit that provides peer support. It has a helpline, peer mentorship programs, support groups, and a treatment directory.

- National Institute of Mental Health. This branch of the National Institutes of Health has information on eating disorders signs and symptoms, risk factors, treatments, studies, and downloadable pamphlets and publications.

- F.E.A.S.T. (Families Empowered and Supporting Treatment for Eating Disorders). An international nonprofit organization helping people who have loved ones with eating disorders. It has information for parents and links to support sources around the world.

- National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. Offers support to anyone in a suicidal crisis or experiencing emotional distress. 800-273-TALK

Sources

Medical disclaimer:

Sunshine Behavioral Health strives to help people who are facing substance abuse, addiction, mental health disorders, or a combination of these conditions. It does this by providing compassionate care and evidence-based content that addresses health, treatment, and recovery.

Licensed medical professionals review material we publish on our site. The material is not a substitute for qualified medical diagnoses, treatment, or advice. It should not be used to replace the suggestions of your personal physician or other health care professionals.