There is a mental health crisis in the United States, perhaps exacerbated by COVID-19 and related concerns (social isolation, joblessness).

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, the percentage of American adults reporting symptoms of anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, or both has almost quadrupled, from 11% January through June 2019 to 41% in January 2021.

The greater problem is the lack of access to and availability of mental health services, especially for vulnerable populations such as ex-offenders.

How many people get incarcerated?

People who have been convicted of crimes and spent time in jails or state and federal prisons are also known as ex-cons, ex-prisoners, the formerly incarcerated, parolees, and returning citizens.

Every year, more than 600,000 are released, but more than three times as many are locked up. A 2020 report calculated that almost 2.3 million persons are confined by the American criminal justice system annually, including:

- 1,291,000 in state prisons

- 631,000 in local jails

- 226,000 in federal prisons and jails

Not all of those individuals have been convicted. Individuals who are arrested spend time in jails until they make bail or their trial ends. Of the 631,000 in jails, more than 467,000 or 74% can’t afford bail and remain in pretrial detention.

According to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), pretrial detention greatly increases the likelihood of conviction and the length of sentence. Detention for a single day or longer also increases the chance that the defendant will not show up for the court date and so be re-arrested.

Persons are not sentenced to jail for more than a year. They may only be there for a few hours at any one time. Some return many times over a year, however. On average, jails hold 612,000 people on any given day but process 10.6 million arrests annually.

Risk of recidivism

Punishment alone will more likely result in repeat offenses and a return to imprisonment. This costly and vicious circle is known as recidivism. Preventing such recidivism is known as desistance.

Time in prison is not usually a one-time occurrence. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, in the first three years after release, two-thirds of ex-offenders are arrested again, and more than half are incarcerated.

Recidivism rates vary by state, ranging from 21.4% in Texas to 66.4% in Alaska.

No one denies that crime should be punished, but punishment, such as incarceration, has several purposes, primarily:

- Separating offenders from society.

- Deterring offenders (and, by example, other citizens) from committing new offenses in the future.

- Rehabilitation to prepare the ex-offender to contribute to and function in society.

(Although rehabilitation is sometimes still cited as a goal of punishment, the concept was dealt a blow by sociologist Robert Martinson in 1975, who charged that rehabilitation did not work. He later modified that opinion and claimed that policymakers had misunderstood his recommendations, but the damage was done.)

What is social reintegration?

Another term for rehabilitation is social reintegration, though perhaps social integration is more accurate. Many ex-offenders were never properly integrated into society.

Underlying many of these obstacles to reentry is the stigma of being an ex-offender. When individuals have spent any time in prison, society may regard it as a legitimate reason to shun them, to not hire them (untrustworthy!), help them get educated (unintelligent!), and not let them live in the same neighborhood (dangerous!).

Often this becomes self-stigma, resulting in low self-esteem, unhealthy behaviors, and poorer mental health symptoms. Stigmatized ex-offenders may give up, stop trying, or even see a return to prison as their only option.

Other obstacles and risk factors to social reintegration include getting a job. A 2002 study found that only 12.5% of employers would seriously consider an ex-offender for a job. That may have changed, however.

According to a 2018 survey, many more managers and human resources professionals were willing to consider a qualified candidate who had a record. The rates differed widely based on the type of crime committed: from 65% or greater for substance use disorder and misdemeanor offenses to about 10% for sexual assaults.

Having a job does not always protect against reoffending. It takes satisfactory jobs that let the ex-offender feel they have some control.

- Earning a living. It can be difficult for ex-offenders to find a job that will pay a living wage. They may not have had such employment before incarceration or the necessary legal marketable skills. Afterward, they can expect to earn 40% less. Promoting education and job training can help.

- Lack of education. A 2014 RAND Corporation report found that any type of education—remedial, vocational, or college-level—undertaken in prison made inmates up to 43% less likely to reoffend and 48% more likely to find a job. According to a 2019 report, however, only 9% of inmates complete a college-level program, and only 42% complete any education program.

- Finding housing. Homelessness may be a risk factor for becoming a convict. A 2002 analysis found that 15% of prison inmates were homeless in the year before their arrest. They are about 10 times more likely (2%) than the general population (0.21%) to be homeless after release.

A 2020 report on the effect of housing on recidivism in San Francisco found that lacking a residence immediately upon leaving prison was associated with a 35% greater recidivism risk. Homelessness during probation increased the risk by 44%.

While housing stability was generally seen as protection against recidivism, however, sometimes ex-offenders benefited from moving even a small distance away from people and places associated with their criminal past.

- Problems relating to family and friends. People are social animals. Without contact with their social network, mental health suffers. They may have a hard time relating to people who don’t share their experiences and remain guarded, wary, like returning soldiers with PTSD.

- Parole violations. Probation (instead of prison) and parole after release from prison are important elements of the punishment/rehab process. They also are part of the re-incarceration process, often needlessly.

A 2019 analysis found that 25% of state prison admissions were for technical violations of probation (11%) or parole (14%)—missing an appointment with their parole officer, not finding a job—rather than new crimes. This is not only costly to the taxpayer—keeping an inmate in state prison costs an average of $33,274 annually in 2015—but detrimental to reintegration.

Health status before, during, and after prison

Analysts find a clear link between health, physical and mental, and both incarceration and recidivism. It’s not just a matter of good health or bad, however.

People who are arrested, jailed, and imprisoned are more likely to have worse health, including a higher incidence of diabetes, high blood pressure, HIV, as well as substance use and mental health problems.

For some inmates, those without access to regular meals or healthcare, physical health may improve while in prison. Most will have poorer overall health and higher rates of infectious and sexually transmitted diseases than the non-prison population due to:

- Unhealthy food. A lot of it is high-fat rather than healthy to better meet minimum calorie requirements at the lowest cost. In some institutions, it comes in only two meals per day and starvation portions.

- Smoking. Although banned in most prisons, it still happens, with all its negative effects on health. In some jurisdictions, prison staff, concerned about inmate violence, are beginning to allow it again. Nonsmokers are exposed to secondhand smoke with all its health deficits.

- Overcrowding and poor ventilation. When prisoners are in close quarters and the air doesn’t flow well, it can lead to the transmission of infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis, influenza, and the Delta variant of COVID-19.

- Violence. About 10% of state prison inmates were injured in a fight, and 9.6% were sexually abused by another inmate or prison staff.

- Stress. While stress is largely a mental condition, it can cause or exacerbate acute and chronic physical health problems such as hypertension, heart disease, chest pain, and a weakened immune system.

Individuals with poorer physical health are more likely to be incarcerated, but those with better physical health in prison and after release are more likely to reoffend.

These are usually violent offenders, who are already more likely to rearrest and may need to be in good physical shape to commit their crimes.

Another possibility is that physically fit inmates don’t seem to need as much help as less fit ones, so prison staff doesn’t allocate them as much of their limited rehab resources.

Mental health before, during, and after prison

As bad as incarceration can be for physical health, it can be even worse for mental health.

The mental health of incarcerated individuals is consistent for ages 18 to 64 but differs by numbers and percentage according to how mental illness is judged.

If the standard is prisoners who have ever been diagnosed with a chronic mental health disease, the rate is approximately 40%—44% in jails, 37% in state and federal prisons— according to 2011–2012 data. If the standard is reports of serious psychological distress within the past 30 days, the rate drops to 26% in jails and 14% in state and federal prisons.

If the standard is reports of serious psychological distress within the past 30 days, the rate drops to 26% and 14%. (A 2014 study found 20% of people in jails and 15% of people in state prisons have mental health disorders.)

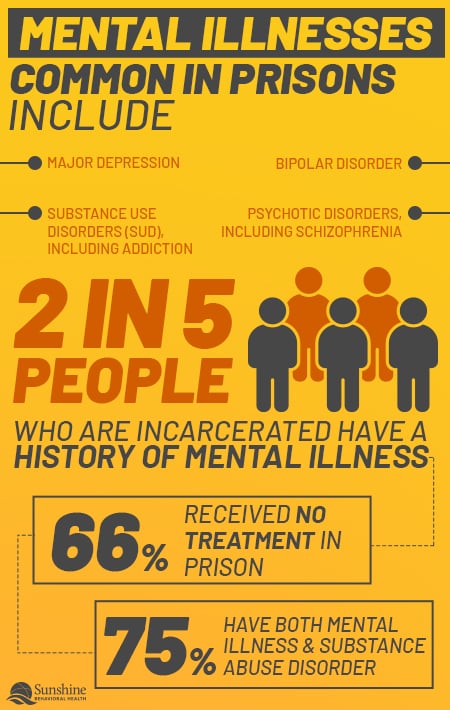

Of those with mental health disorders, 66% say they received no treatment while in prison.

According to a 2014 survey, approximately 356,000 inmates in jails and state prisons—15%–20%—have serious mental illnesses compared to just 35,000 in state psychiatric hospitals. Most observers think the disparity has only grown since then.

Not all cases of mental illness are rated serious. The rate for any mental illness is 37% and 1.2 million inmates. The rate is even higher in local jails at more than 44%. Mental health care was not even offered to 66% of federal prison inmates. Further, there is some correlation between having less access to mental health services and higher rates of people in prison.

The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) says that individuals with mental illnesses are arrested and placed in jail every year 2 million times, though not all are convicted or serve long sentences.

Many prison and jail inmates—a minority of them, but still a significant number—have a mental health problem because they had it before they were arrested. It probably wasn’t treated while they were incarcerated, so they are likely to still have it after their release.

What is Mental Illness?

Mental illness is when your thoughts, feelings, and behavior affect your ability to take care of yourself and your daily responsibilities, such as:

- To go to school or work

- To maintain social relationships

- To pay bills, shop for groceries, maintain your property

- To feed and clean yourself.

Stress, trauma, and genetic factors can cause mental health issues, concerns, and disorders. Mental illness results when these issues aren’t addressed early enough or at all.

People in state prisons are more likely to have mental health disorders than the general population and also more severe psychoses and major mood disorders. About 20% have a serious mental illness (SMI) and 30%–60% have a substance use disorder (SUD). Those rates increase when you consider all mental illnesses requiring treatment, not just SMI.

Mental illnesses common in prisons include:

- Major depression

- Psychotic disorders, including schizophrenia

- Bipolar disorder

- Substance use disorders (SUD), including addiction

Even those without diagnosable mental illness face threats to their mental wellness. Whether in local jails or federal or state prisons, inmates are more likely to experience depression, other mood disorders, and other mental health issues, including:

- Anxiety

- Stress

- Bipolar disorder

- Flashbacks

- Suicidal ideation

- Substance use disorder

- Trauma, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

If offenders have these mood disorders, substance use disorder problems, or other mental health issues when they arrive in prison, they are unlikely to get better. They rarely offer adequate or effective treatment. Instead, imprisonment may exacerbate them. Worse, an inmate may develop mental health issues while in prison.

What is Addiction?

Addiction is the most severe form of SUD. It is when one uses alcohol, illicit or prescription drugs, and other substances because one has to, not because one derives pleasure or benefit from it.

Many people still believe that addiction is a sign of weak character or a lack of willpower or morality, but Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health (2016) said: “addiction is a chronic neurological disorder” or disease that “needs to be treated as other chronic conditions” such as cancer, diabetes, and heart disease, with skill and compassion.

Addiction changes the wiring of the brain because these substances produce elevated levels of feel-good chemicals. The brain suffers because:

- It stops producing these chemicals.

- It gets used to the artificially high levels of substance use disorder.

- If the substance use stops, it feels physical and/or psychological pain known as withdrawal.

- The dosage required to stop the pain increases over time as tolerance builds.

Eventually, it may become nearly impossible to take enough of the substance to do more than stop the pain without causing a fatal overdose.

In some extreme cases with certain substances (mainly alcohol and benzodiazepines), withdrawal can be not only painful but lethal.

Dual Diagnosis

NAMI doesn’t consider substance use disorders or addictions as mental illnesses but acknowledges that they often go together and there are causal links. This is a dual diagnosis.

Comorbidity or co-occurring disorders is a term for when someone has two conditions at the same time that are linked in some way. When those two conditions are a SUD and another mental health issue it is called a dual diagnosis. When that happens, both conditions must be treated.

Sometimes a mental illness leads to a SUD because the individual knows something is wrong and is trying to self-medicate with alcohol or drugs. In the past, substance use disorder counselors didn’t check for a co-occurring mental illness and only treated the SUD. In such cases, relapse is more likely because the underlying cause of the SUD remains.

The same applies to people leaving prison or jail. To avoid a revolving-door justice system where people are released with the expectation that they will be re-incarcerated, offenders should be screened before they enter prison and receive treatment while in prison. They should be screened again as they leave prison, and have a treatment that follows them into their re-entry.

What Causes Mental Illness?

There is no single cause for mental health disorders. The most likely explanation is multiple factors, such as:

- Genes. You may have a genetic predisposition in your family history.

- Lifestyle. You engage in risky behaviors that result in traumatic brain injuries, long-term substance use disorder, or drug overdoses. Or you have a job that causes stress and anxiety.

- Childhood Abuse. Psychological or physical violence, possibly sexual.

- Serious Medical Conditions. Cancer, heart disease, epilepsy, stroke, HIV.

- Social Isolation. Lack of friendships or family relationships.

The question remains: Does imprisonment lead to mental illness? Cause mental illness? Exacerbate mental illness? Or are metally ill people drawn to crime?

There is no clear answer as to whether incarceration can cause one to become mentally ill. Analysts disagree. Regardless, no one says incarceration is good for mental health.

Risk factors for poor mental health in prison

Prison conditions that contribute to poor mental health include:

- Being told when to wake up, go to sleep, eat, exercise, and relax.

- Loss of privacy due to overcrowding.

- The trauma of witnessing or experiencing violence.

- Isolation from family and friends.

- Solitary confinement.

People who are locked away from everyone, even for their protection, may suffer mood disorders and other mental problems that may result in hallucinations, self-injury, and suicide. When people are visited by family and friends in prison, recidivism rates decrease by 26%.

The Movement Towards Deinstitutionalization

The reason that there are so many individuals with mental illnesses in prison is that there are so many individuals with mental illnesses on the street.

Dating back to the 1950s, due to well-intentioned psychiatric professionals, civil rights advocates, and some well-publicized abuses, the trend has been away from placing clients with mental health issues into specialized hospitals and towards deinstitutionalization.

The thought was that most of these individuals could remain in society with a little help, such as regular visits with a psychiatrist and medication to control their symptoms.

Without sufficient funds, however, these individuals many times fell through the cracks. Many were arrested and incarcerated without being screened for mental illnesses.

Some became homeless. At least 25% of homeless individuals have a serious mental illness. To “solve” the homelessness problem, many communities have criminalized homelessness.

Most criminal behavior isn’t caused by mental illness, but mental illness can lead to criminal behavior. The perception is that people with mental health issues are violent and can’t be released into the community. Since adequate mental health treatment services frequently aren’t available, the state may feel that prison incarceration is the only option.

The problem is that incarceration won’t improve mental health, or stop substance use.

Mental Health Care in Prison

If mental illness doesn’t have a single cause, neither does it have a single treatment. Whether the mental health disorder is a psychosis, depression, anxiety, or SUD, the answer is probably a combination of therapy and medication-assisted treatment (MAT).

The Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) is and has been aware of the problem of mentally ill prisoners. In 2014, it promised better care and oversight for inmates with mental health issues, but no new resources were provided. Instead, care was reduced by more than 35%. In some areas, the number of inmates getting treatment dropped 80% or more.

By 2018, the BOP concluded that only 3% of its inmates needed regular care for mental health issues.

(State prison systems disagreed. Upwards of 20% of inmates got treatment in Texas, New York, and California.)

Part of the reason may be that the BOP considers counselors and social workers in prison as primarily “professional law enforcement officers,” not mental health care workers, and so were redirected to other jobs. There are reports that prison psychologists were sometimes stationed in gun towers and assigned to escort prisoners.

Another reason may be that many judges, politicians, and old-school physicians think that the use of drugs equals addiction. If you must take the drug every day, isn’t that an addiction?

No, not if it allows you to function in society: take care of your hygiene and home, hold down a job or go to school, drive and shop, pay your bills. Diabetics who use insulin aren’t addicts, nor are people who take blood thinners to avoid blood clots.

How Does Incarceration Affect Inmates?

Not everyone who spends time in prison is mentally ill or becomes mentally ill. If they go in with no serious mental illness, any harm caused is probably not permanent. That doesn’t mean they aren’t affected, even damaged.

Imprisonment is unnatural. To be confined for months or years is not pleasant, but one can and must become accustomed to it to survive. That’s not necessarily a mental illness, but it can make returning to the outside world difficult.

Long-term incarceration may result in:

- Reliance on the structure of prison.

- An inability to trust anyone.

- An unwillingness to show emotion.

- Withdrawal from social interaction.

- Accepting rules of prison life as the norm.

- Lack of self-worth.

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Especially damaging is solitary confinement. Whether for punishment or protection, prolonged isolation can result in hallucinations, depression, panic attacks, suicidal ideation or acts, and other mental or physical harms.

As the experience gets worse, so does the likelihood of long-lasting harm. This is why decompression—the gradual re-acclimation of prisoners to life outside—is so important. Unfortunately, direct release without much preparation is the norm.

Benefits of Mental Health Care in Prison

Returning to non-prison life requires an adjustment period, something more than showing the ex-offenders the door with a few bucks in their pockets. It’s worse for people with mental health issues.

You can’t cure mental illnesses, not even addiction, simply by locking someone up. Without comprehensive treatment, substance use may stop while imprisoned but resume with the first trigger or opportunity. Such a return to using can be fatal because of diminished tolerance.

Sometimes that substance use not only doesn’t stop while in prison; sometimes that’s when it starts. Like first-time offenders who leave prison with diminished employment prospects but a lot of new criminal skills, ex-offenders can leave with a substance use disorder they didn’t have going in.

NAMI has several programs designed to keep people with mental health disorders out of jail or prison, to help them receive treatment while there, and to help their families and friends navigate the criminal justice system.

Better Mental Health, Less Recidivism

It’s in everyone’s interest to ensure mental health treatment for individuals before, during, and after incarceration.

Individuals with mental illnesses are more likely to worsen or relapse after imprisonment, so it would be good for them to go into or continue treatment upon release.

It would be better if they could get mental health treatment while imprisoned, so they could smoothly segue into aftercare. It would be best if they could get treatment before they ended up in the justice system in the first place.

The next best solution is for ex-offenders to find help upon their release.

Providing access to mental health services in prison reduces the likelihood that inmates will attempt suicide. It also makes it more likely that they will become healthy, productive members of society when they leave prison.

Ex-offenders were more likely to have better mental health after incarceration if treatment begins during (or before) incarceration and there is assistance in continuing treatment on the outside.

Lower Financial Costs to Society

If that doesn’t motivate authorities, it also saves money.

When budget cuts are deemed necessary, prison treatment is seen as a safe cut, because authorities feel most people won’t be upset if criminals lose some amenities. This is short-sighted because prisoners who don’t get mental health treatment in prison or jail are more likely to require:

- Longer incarceration.

- More staff.

- Isolation from the general population.

- Expensive psychiatric medications.

- Contesting lawsuits for neglect or wrongful death.

All of these consequences cost money.

A 2010 National Center on Addiction and Substance Use Disorder report estimated that each inmate who remains sober, employed, and crime-free would save $91,000 per year.

In 2011, the National Institute on Drug Abuse estimated that the cost to society of drug-related crime was $113 billion. The cost of treating drug abuse would have been $14.6 billion.

Lower Mortality

An SMI or SUD, alone or as a dual diagnosis, can both result in death, either accidentally (a motor vehicle mishap, an accidental overdose, an alcohol-drug interaction) or deliberate, i.e. suicide.

Not all suicides are due to mental illness. An increasing number seem to be “deaths of despair”: individuals whose life plans have gone so far off the rails (unemployment, money problems, isolation due to a drug habit, divorce, or COVID-19 social distancing) that they see no way out.

In 2015, a Swedish study found that newly released prisoners committed suicide 18 times more often than the general population, especially in the early months. Risk factors included having attempted suicide at least once and past psychiatric disorders, especially SUD.

The researchers suggested authorities should help ex-offenders transition to life outside prison and provide clinical monitoring to reduce the risk of relapse in the early months.

Mental Health Treatment for Ex-Offenders

If ex-offenders didn’t get help for their mental health disorders or SUD in prison, decompression is going to be much harder and relapse more likely. That doesn’t mean they should give up.

Fortunately, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA or “Obamacare”) requires that “All Marketplace plans cover mental health and substance use disorder services as essential health benefits,” as well as pre-existing conditions. If you had SMI or SUD before prison, you are still entitled to coverage as an ex-offender.

Specifically, all marketplace plans must cover:

- Behavioral therapies or other counseling methods. These are “talk therapies” designed to teach healthy ways to respond to life’s problems.

- Inpatient services. Sometimes clients need immersive treatment to control or prevent triggers that led to their mental illnesses.

- Medication-assisted treatment (MAT). Sometimes the right drug, in the proper doses, can control the symptoms of mental health disorders, including some SUDs.

Mental Health and Recidivism

While good physical health seems to lead to an increase in recidivism, so does poor mental health. Even the most humane lockup causes psychological damage. If the prisoners had mental health issues before jail or prison, they will likely become worse.

Post-incarceration syndrome is a subset of PTSD (not yet recognized by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) in which the ex-inmates still feel and behave like inmates: detached, hard, alienated, and almost paranoid.

People who spend time in prison become institutionalized. They internalize the rules and restrictions forced upon them, both formal and those learned from living in the prison environment. This process is dehumanizing and bad for their mental health.

Because their choices have been circumscribed for so long, they may have poor decision-making skills and a sense of direction. They also may have trouble reading body language or gauging other people’s intentions.

Since incarceration seems to lead to poorer mental health, imprisonment—even for a day in jail—is a risk factor for recidivism, leading to higher numbers of repeat offenders, including multiple arrests within the same year.

According to a 12-month follow-up, 27% of people with a reported mental health disorder were jailed at least three times. That’s three times as many as the 9% who were never arrested.

Substance use disorder and recidivism

A report found that in 2006, 65% of inmates in US prisons had alcohol or drug use disorders. An additional 20% committed their crimes to get the substances or while under the influence of these substances.

In 2017, about 20% of all US prisoners—local, state, and federal—were imprisoned on drug charges.

A 2014 article found high rates of recidivism among former inmates who used drugs. Within three years of release, 68% were arrested again.

Co-occurring disorders and recidivism

Mental illness and substance use disorder both lead to higher rates of recidivism. Worse, they often co-occur, making recidivism rates higher still.

According to 2017 data, about 7.7 million adults had such co-occurring disorders, including two-fifths (37.9%) of adults with substance use disorders and almost one-fifth (18.2%) of those with mental illnesses.

A 2006 analysis found that of people incarcerated, 75% had both a mental illness and a substance use disorder.

In one 2013 analysis of 9,669 newly released inmates in New Jersey:

- 4,005 (41.4%) has a substance use disorder

- 1,175 (12.2%) had mental health problems

- 1,020 (10.6%) had both

The New Jersey study, along with other studies—including a large 2008 study in Texas—strongly suggest that rates of recidivism are higher among people with a dual diagnosis of mental illness and substance use disorder than either disorder alone. The Texas study also found a higher risk of multiple incarcerations over six years.

Reducing recidivism requires treatment of both mental health disorders and substance use disorders by experts who can recognize when they co-occur.

Since it may be difficult to get mental health treatment without a place to live, some housing may also be available, including public housing, transitional housing, and supportive housing.

If you can’t find these services on your own or need other services to decompress after incarceration, organizations are willing to help.

Prison Reentry Programs

Mental health is not the only problem facing former inmates, but by helping their reentry into society, these programs may improve mental health and decrease the likelihood of reoffending and reincarceration.

Mental health is not the only problem facing former inmates, but by helping their reentry into society, these programs may improve mental health and decrease the likelihood of reoffending and reincarceration.

In 2018, former National Institute of Justice Director David Muhlhausen called for more research to devise evidence-based reentry programs, stating that no existing ones qualified.

The Bureau of Prisons (BOP)

This government agency is charged with keeping prisoners locked up—securely, safely, and humanely—but also with assisting their successful reentry into society following release.

The BOP programs that help inmates acquire valuable skills and work experience are:

- Federal Prison Industries. Also known as UNICOR, this program allows inmates to learn vocational skills and earn money (up to $1.15 an hour). A BOP study concluded that participants were 24% less likely to reoffend or be rearrested, even 12 years later. They were also 14% more likely to find employment adequate for their needs.

- Release Preparation Program. BOP’s stated goal is to begin release preparation on the first day of their incarceration, but it intensifies in the 18 months before release with classes or practice covering:

- Résumé writing.

- Job search and retention.

- Job interview skills.

- Job training opportunities.

- Residential Reentry Centers. Also known as halfway houses. To ease ex-inmates back into society, they may spend time in a monitored facility with further reentry programs, including employment counseling, job placement, and financial management assistance.

Volunteers of America

This nonprofit provides Correctional Re-Entry Services, including:

- Specialized Case Management Services. Intensive supervision and support for qualified first-time or targeted offenders—DUI (Driving Under the Influence), domestic violence—so they may avoid pretrial detention.

- Residential Treatment. Cognitive-behavioral treatment approaches, 12-step, and relapse prevention services.

- Community Sanction & Re-Entry Centers.

- Literacy and other educational training

- Life skills training

- Assistance finding housing

- Alcohol and substance use disorder treatment

- Case management

- Day Reporting. Community center-based service opportunities for low-risk offenders.

Other related services include substance use disorder and mental health. Veterans Affairs provides helpful information for veterans, even formerly incarcerated veterans with mental health issues, including: Prison Fellowship, a faith-based nonprofit, provides for the spiritual and physical needs of those in prison (and their families with its Angel Tree program), as well as advocating for criminal justice reform. Its Prison Fellowship Academy offers an intensive, biblically-based program in some correctional institutions and occasional one- or two-day Hope Events. Prison Fellowship also offers a list of national organizations that provide essential reentry services, plus some guidance on possible state and local resources. Catholic Charities USA: Assistance for those dealing with poverty and homelessness. Goodwill Industries: Job training and employment services, especially for people with a history of welfare dependency, illiteracy, criminal history, and homelessness. Salvation Army: Its Harbor Light and rehabilitation centers sometimes act as halfway houses for ex-offenders in work-release programs. Also can provide job training, employment opportunities, spiritual guidance, and other material aid. Social Security Administration (SSA): May provide retirement benefits or disability assistance to qualified ex-offenders. U.S. Department of Labor Employment and Training Administration (ETA): Its workforce, one-stop, and job service centers provide job training and placement services for economically disadvantaged adults. United Way: Focused on facilitating financial stability, education, and health. YMCA: Offering help with child welfare, community health, job training, environmental education, and family needs. YWCA: Provides assistance with child care, rape crisis intervention, domestic violence assistance, shelters for domestic violence victims and their families, job training, and career counseling. Inmates and their families should look for similar agencies or organizations in their states, towns, and cities: State: Local: Organizations

Resources for Formerly Incarcerated People

Support for Incarcerated Service Members And Veterans

Other Resources for Reentry Services

National Organizations/agencies

Local and State-Level Resources

Mental Health Resources

Crisis Prevention Lines

Guides

Peer Support Fellowships/Support groups

Sources

Medical disclaimer:

Sunshine Behavioral Health strives to help people who are facing substance abuse, addiction, mental health disorders, or a combination of these conditions. It does this by providing compassionate care and evidence-based content that addresses health, treatment, and recovery.

Licensed medical professionals review material we publish on our site. The material is not a substitute for qualified medical diagnoses, treatment, or advice. It should not be used to replace the suggestions of your personal physician or other health care professionals.