Narcan is a lifesaver — literally — in the ongoing opioid crisis because it can reverse an opioid overdose, at least temporarily, before an individual dies.

Narcan is a formulation of and a delivery system for naloxone, an opioid antagonist that has been around since 1961. Naloxone has been prescribed for opioid overdoses since 1971, but for many years, it was only available as an injection by medical personnel.

Naloxone and other opioid antagonists work by blocking the effects of opioids, potentially stopping the overdose within three minutes. It is not an addictive drug, it does not cause euphoria or overdoses, and it’s legal to carry.

Since 1996, opioid abuse kits have included two doses of Narcan (an injectable form of naloxone hydrochloride), along with two needles. (The second dose is in case the first one doesn’t complete the job.) In 2014, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Evzio, a “hand-held auto-injector” version of naloxone hydrochloride for use by the layperson.

In 2015, a nasal spray application of Narcan and a generic Narcan nasal spray in 2019 made opioid overdose reversal by nonmedical staff easy.

That doesn’t mean immediate medical care for opioid overdoses isn’t still needed. Narcan may not work without a second dose, and that double dose might only last 30 minutes or so. It also causes instant withdrawal that can produce psychological and physical pains.

What are opioids?

Opioids are drugs derived or synthesized from the opium poppy. They include morphine, heroin, oxycodone, hydrocodone, and fentanyl. Some are illegal to prescribe or closely controlled because they can be extremely addictive.

While opioid addiction has been around for a century or more, the introduction of new, supposedly nonaddictive opioid painkillers in the 1990s helped spur the opioid crisis.

Physicians long faced criticism by some for being too reluctant to prescribe pain management medicines for their patients — particularly those with chronic or long-term pain — for fear that they could lead to addiction.

People who use opioid painkillers can quickly develop tolerance: the body chemistry becomes accustomed to the original dosage of the drug, requiring more for it to produce that same painkilling effect.

The human body produces opioids and other feel-good chemicals. Over time, however, opioid medication use outstrips the body’s ability to produce these chemicals, causing it to stop production and making the patient dependent on outside opioids.

A larger dosage becomes needed to make the patients feel normal, let alone feel good, and it becomes almost impossible to stop without going through withdrawal.

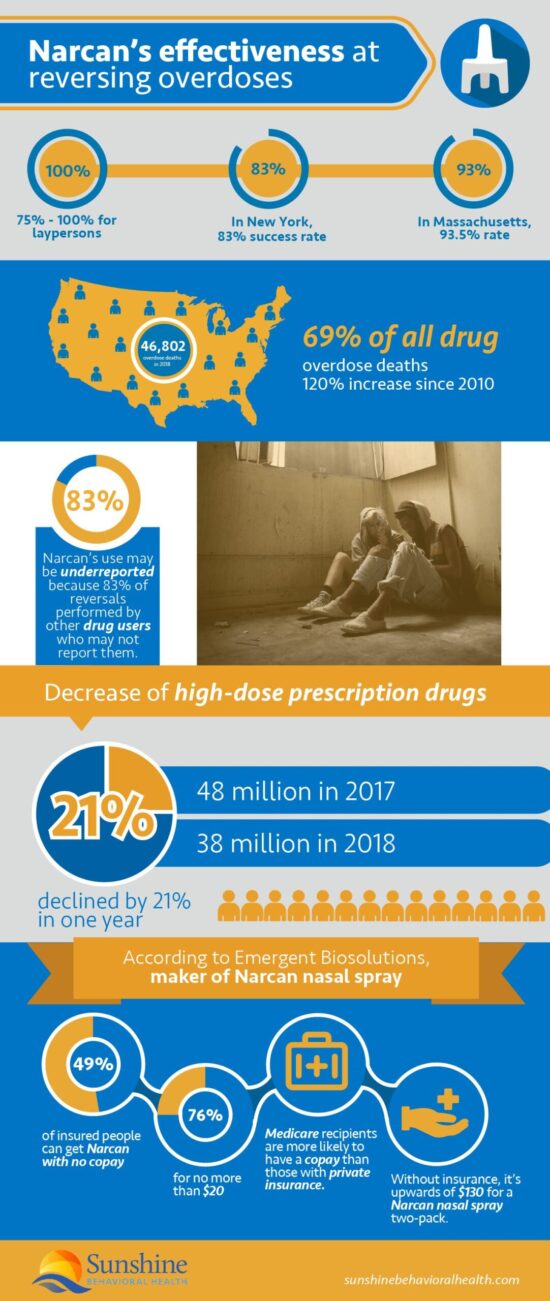

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) determined that there were 46,802 opioid overdose deaths in the United States in 2018, 69.5% of all drug overdose deaths. That was a 120% increase since 2010.

What is an opioid overdose?

An opioid overdose happens when an individual uses more opioids — on purpose or accidentally — than their body can handle.

Since opioids affect areas of the brain that regulate the lungs and breathing, too large or too potent a dose of opioids may cause individuals’ brains to misfire — even longtime users — and slow or stop breathing.

While an opioid overdose is not always fatal, and rarely immediately so, if the brain is deprived of oxygen for as little as four minutes, it may suffer permanent damage.

The risk increases when opioid use occurs at the same time as other drugs:

- Alcohol

- Stimulants

- Illegal (cocaine, methamphetamine)

- Legal (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder drugs such as Ritalin and Concerta)

- Benzodiazepines (Xanax, Klonopin, Valium).

An opioid overdose may also affect the blood, brain, and heart.

How the new opioids led to the Opioid Crisis

Now, with their patients clamoring for more effective painkillers and the pharmaceutical companies promoting the safety of their products, many physicians began to prescribe these new opioids for people with chronic or long-term pain as well as those with acute or short-term pain.

When the new opioids turned out not to be as safe as advertised, medical and law enforcement professionals enacted more severe restrictions, but the damage was already done.

Many people were addicted. Their supply of prescribed, federally inspected, and approved opioids cut off, they turned to the black market. When black-market supplies of these drugs became too hard to obtain, they settled for any opioid.

The number of high-dose opioid prescriptions declined by 21%, from 48 million in 2017 to 38 million in 2018. Prescriptions for naloxone still more than doubled from 270,000 to 556,000.

Some turned to heroin or newer, less expensive, and more potent opioids. One is fentanyl, a rarely prescribed drug readily available on the black market, approximately 100 times as strong as morphine. Another is carfentanil — 100 times as strong as fentanyl — sometimes used as a tranquilizer for elephants and other large animals.

The people with new addictions sometimes didn’t know they were using fentanyl because it was pressed into pill form and sold as oxycodone or mixed with other drugs such as heroin and cocaine, a nonopioid drug. (When stimulant drugs such as cocaine or methamphetamine and an opioid are deliberately combined, it’s known as a speedball. People combine the substances to achieve a bigger rush.)

Because fentanyl is so much more potent that a slight miscalculation by the dealer or the customer can be lethal, opioid overdoses and deaths rose dramatically.

Nevertheless, opioid users and their friends were often reluctant to call 911 when they or someone with them experienced an overdose, possibly for fear of arrest. Even when there were laws to protect them, they were still unlikely to call.

Signs of an opioid overdose

Signs that someone may be experiencing an opioid overdose include:

- Erratic, slow, or difficult breathing or pulse.

- Loss of consciousness.

- Inability to talk or respond despite being awake.

- Skin or fingernails that have turned bluish-purple or ashen-gray.

- Vomiting.

How does Narcan reverse an opioid overdose?

Naloxone is an opioid antagonist. That means it blocks the opioid receptors in the brain. If individuals have been using opioids, it turns off all the pain-blocking or euphoric effects in minutes, causing immediate withdrawal and the associated withdrawal pains if they have become dependent on opioids.

Naloxone is an opioid antagonist. That means it blocks the opioid receptors in the brain. If individuals have been using opioids, it turns off all the pain-blocking or euphoric effects in minutes, causing immediate withdrawal and the associated withdrawal pains if they have become dependent on opioids.

If people are experiencing overdoses, naloxone blocks those extreme effects too. It does not eliminate the opioids from their systems, however. If people with opioid use disorders attempt to overwhelm the naloxone by taking more opioids, it may only compound the unwanted effects.

Naloxone for Opioid Use Disorder

For naloxone to be effective, it should be injected or sprayed into the nasal passages. When swallowed, as in a pill, it has little or no effect.

When combined with the opioid partial agonist buprenorphine in the medication known as Suboxone, naloxone deters misuse and abuse.

Buprenorphine, as an opioid partial agonist, has weaker effects than oxycodone (the opioid drug found in OxyContin and Percocet) and other full agonists, takes effect more slowly, peaks sooner, and lasts longer.

This makes it an ideal medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for opioid addiction, particularly when combined with naloxone as a sublingual tablet or film.

People with opioid use disorders sometimes try to get a more intense high by crushing the pills to snort or dissolving them to inject. When Suboxone is crushed or dissolved for injection, the naloxone in the drug cancels the opioid’s effects.

What to do during an opioid overdose

When someone is present at an overdose, before administering Narcan, the first and most important thing to do is call 911 or obtain other emergency medical assistance. The overdose may not result in death for hours, and Narcan may not always help.

More importantly, they still need professional medical help. It is not safe to assume that the risk of overdose and death is over after using Narcan. Follow any advice or instructions offered by the operator. If people know which drug or substances contributed to the overdose, they should tell the emergency operator.

Most Narcan kits for laypeople contain two doses of the drug, but opioids such as fentanyl may require several or an IV drip. One woman died despite three doses of Narcan.

Second, make sure the people overdosing can breathe. Check their mouths for any obstructions, even chewing gum. If their breathing is erratic, mouth-to-mouth might be necessary. Then, lay them on their stomach, head turned; there’s less chance of the airway becoming blocked.

Next, administer the first dose of Narcan. Full instructions are with the kit. Tilt the head back, place your hands on the person’s forehead and chin. Spray about half the applicator into one nostril, then do the same with the other nostril. If there’s no response after 5 minutes, repeat with the second dose.

Finally, they should not be left alone until after medical help has arrived because:

- If breathing stops before help arrives, mouth-to-mouth or CPR might save their lives.

- If the reversal works, they may experience withdrawal and use the drug again to stop the pain. That might be fatal.

Sometimes bystanders and even first responders have been reluctant to give aid for fear of lawsuits if something goes wrong. Good Samaritan laws in most U.S. states protect those who try to save lives, even if they have also been using drugs.

How effective is Narcan?

Narcan has proven highly effective at reversing overdoses short of death, even when administered by laypeople. In 19 assessments, the efficacy of community-based opioid overdose prevention programs (OOPPs) was between 75% and 100%.

New York reported an 83% success rate. In Massachusetts, authorities recorded a 93.5% rate, with 84.3% people still alive a year later.

The rate may be higher. Other drug users perform an estimated 83% of reversals and may not report them.

Narcan only works for opioid overdoses, however. There are few overdose reversal agents for other drugs that are as effective as Narcan is for opioids.

Where is Narcan available?

When naloxone is more readily available, opioid overdose deaths seem to decline. The release of Narcan makes it easier for anyone to administer, providing Narcan is on hand.

Some harm reduction experts have proposed handing out a prescription for Narcan with every prescription of opioids. Others have proposed safe injection sites where people can bring and use their opioids, with a medical practitioner on hand to administer naloxone if needed.

Between 1996 and June 2014, Narcan kits were made available to 152,283 laypeople. By June 2014, they had reversed 26,463 overdoses.

This did not include the number saved by professionals such as law enforcement, firefighters, or emergency medical services. Most first responders started carrying Narcan because people sometimes died before an ambulance could arrive.

Another front on the overdose reversal battle has been public libraries, whose staff often have Narcan on hand because they have been the site of many overdoses.

Currently, many (maybe all) CVS, Walgreens, Rite Aid, and Kroger will dispense Narcan without a prescription. Other pharmacies, chain and independent, may do likewise.

How much does Narcan cost?

The cost of Narcan varies. Insurance often covers it, though there may be a copay.

According to Emergent Biosolutions, maker of Narcan nasal spray:

- 49% of insured people can get Narcan with no copay.

- 76% with a copay no more than $20.

- Medicare recipients are more likely to have a copay than those with private insurance.

- Without insurance, the cost is upwards of $130 for a Narcan nasal spray two-pack.

Resources on Naloxone (Narcan)

For more information on Narcan:

Substance Use Disorder and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

MedlinePlus, a service of the National Institutes of Health’s National Library of Medicine (NLM)

National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

- U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on Naloxone and Opioid Overdose

- Naloxone: The Opioid Reversal Drug That Saves Lives

Sources

Medical disclaimer:

Sunshine Behavioral Health strives to help people who are facing substance abuse, addiction, mental health disorders, or a combination of these conditions. It does this by providing compassionate care and evidence-based content that addresses health, treatment, and recovery.

Licensed medical professionals review material we publish on our site. The material is not a substitute for qualified medical diagnoses, treatment, or advice. It should not be used to replace the suggestions of your personal physician or other health care professionals.