Working as a police officer can be hazardous to a person’s health. In addition to dangers caused by violent situations, accidents, natural disasters, and other factors, police officers face a grave danger that people sometimes overlook: suicide.

Statistics About Police Officers and Suicide

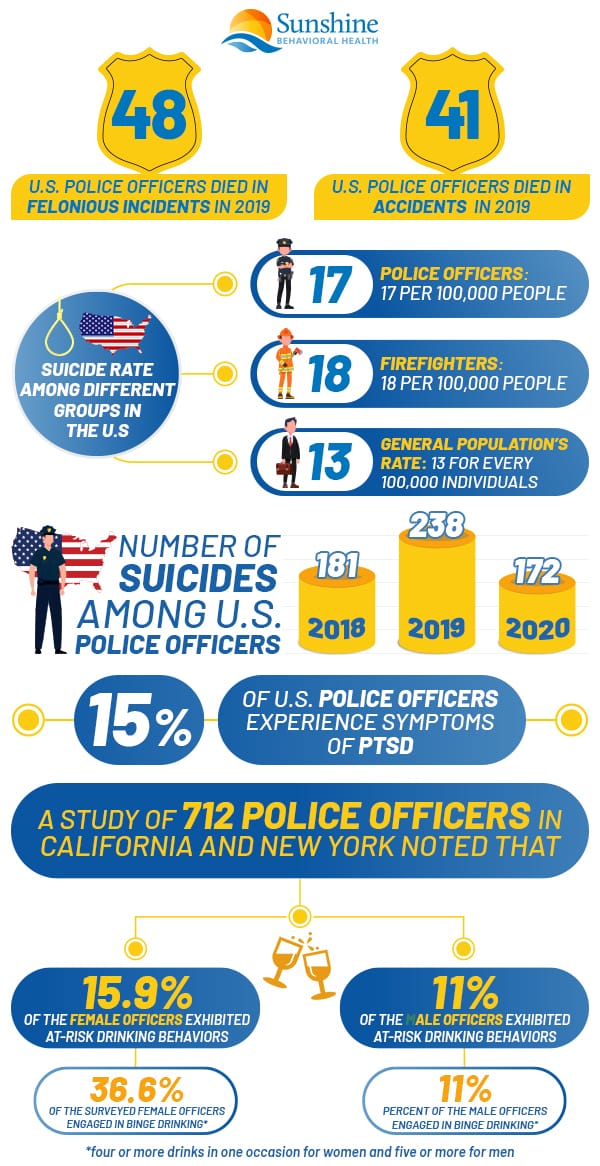

Statistics have indicated that suicide poses a greater risk to a police officer’s health than on-the-job dangers. The organization Blue H.E.L.P. stated that hundreds of U.S. police officers have died by suicide since 2018:

- 2018: 181 officers died by suicide

- 2019: 238 officers

- 2020: 172 officers

Compared to the 238 officers who took their own lives in 2019, 48 officers in the United States died in the line of duty in what the Federal Bureau of Investigation calls felonious incidents. Another 41 died due to on-the-job accidents.

Such numbers are higher than most other professions. The suicide rate for police officers is 17 per 100,000 people, according to the Ruderman Family Foundation. The rate for firefighters is slightly higher, at 18 per 100,000 people. Meanwhile, the general population’s rate is 13 for every 100,000 individuals.

First responders work in professions that elevate the risks of suicide on and off the job.

Police Mental Health and PTSD

Police officers and firefighters might participate in, witness, or see the aftermath of assaults, accidents, natural disasters, and other threats to their physical and mental health. Such threats could cause trauma.

Exposure to trauma could trigger a condition known as post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD. People with this disorder constantly relive the traumatic incidents in their brains. These replays could cause:.

- Flashbacks or nightmares that revisit the events.

- Avoidance of people, places, and things that remind them of the incidents.

- Anxiety and extreme alertness to the signs of possible danger.

Traumatic incidents produce stress when they’re occurring. When people have PTSD, these events continue to produce stress, sometimes long after they’re ended.

Since their jobs can be extremely stressful and dangerous, police officers often develop PTSD. According to the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS Office), about 15% of U.S. police officers experience symptoms of PTSD. This office emphasizes that this number is an estimate, so the real extent of the problem is unknown.

PTSD’s connection to suicide is better known. In fact, there’s a strong connection between the two.

Researchers studying suicide in Sweden reported that

- Women with PTSD had a 6.74% higher suicide rate than the general population.

- Men with PTSD had a 3.96% higher suicide rate than the general population.

- PTSD caused up to 53.7% of the suicides among people with PTSD.

- PTSD caused 3.5% of suicides for women and 0.6% of suicides for men.

Treating PTSD, then, might help prevent suicide as well.

Police Mental Health and Substance Use

Whether police officers have an official diagnosis of PTSD or not, some try to cope with their symptoms on their own. If they use alcohol or drugs for this purpose, they’re engaging in a practice called self-medication.

Self-medication is dangerous for a number of reasons. Alcohol and drugs can affect healthy people’s bodies and brains. If people have PTSD or another condition such as depression or anxiety, these substances can make things worse.

Drug and alcohol misuse and PTSD are linked. One study of 124 individuals who were dependent on substances found that 71 had diagnostic characteristics for PTSD.

Other researchers have noted a connection between alcohol and police culture. One study of 712 police officers in California and New York noted that:

- 15.9% of the surveyed female officers and 11% of the male officers exhibited at-risk drinking behaviors, drinking an average of 35.31 drinks in the previous week. At-risk drinking behavior was defined as more than seven drinks a week for women and more than 14 a week for men.

- 36.6% of the surveyed female officers and 37.2% percent of the male officers engaged in binge drinking. For women, the study defined binge drinking as the consumption of four or more drinks during a single occasion. For men, binge drinking was the consumption of five or more drinks during a single occasion in the past month.

Alcohol and drug misuse are also linked to suicides. Studies have found that

- 25% or more of the people who have addictions to alcohol or drugs kill themselves.

- More than 50% of suicides have connections to alcohol and drug dependence.

- More than 70% of the suicides among adolescents might relate to the use of alcohol and drugs or dependence on those substances.

If police officers misuse alcohol or drugs or are addicted to them, they might face a higher risk of taking their lives.

Dismantling the Code of Silence

By using alcohol or drugs to treat PTSD and other conditions, police officers are self-medicating. They could be doing so because they’re afraid to seek outside help.

Officers might be worried about what others will say if they disclose their problems or mention that their fellow officers might be suffering. They could be worried that their disclosures could stigmatize them and affect their jobs.

An unspoken code known by names such as the Code of Silence and the Blue Code of Silence has deterred some officers from talking about their or their fellow officers’ struggles. But not discussing substance use disorder, PTSD, substance use disorder, suicidal thoughts, and other issues means that other people won’t know about them, so they’re likely to worsen.

Talking about suicide and mental illnesses can help reduce the stigma surrounding them. It can reassure people that they’re not alone and it can help them find compassionate, experienced treatment.

To talk about such issues, organizations and initiatives have been raising awareness of police officers’ problems and working to solve them. Some resources include:

Resources on Mental Health for Police and their family

- Badge of Life – Using the slogan, “Building a better cop,” Badge of Life is an organization committed to preventing suicide and providing mental health resources for law enforcement officers and their loved ones.

- Blue H.E.L.P – Blue H.E.L.P. is an organization that aims to provide law enforcement workers information about mental health and ease the stigmas surrounding it, acknowledge officers who have taken their lives, and advocate for PTSD benefits.

- Breaking the Silence on Law Enforcement Suicides – This symposium by the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) acknowledges that the code of silence hurts officer wellness and makes recommendations to prevent suicides and bolster mental health.

- CopLine – By calling the hotline 800aCOPLINE (800a267a5463), active or retired law enforcement officers can talk to retired law enforcement officers about mental health matters without stigma.

- Law Enforcement Mental Health and Wellness Act (LEMHWA) of 2017 – Signed in 2018, this legislation strives to make mental health and wellness assistance for law enforcement officers more accessible.

- LEO Near Miss – Law Enforcement Officer (LEO) Near Miss is a website that allows law enforcement officers to anonymously report incidents where they could have been killed or seriously injured.

- National Consortium on Preventing Law Enforcement Suicide Toolkit – Another offering from the IACP, this kit includes resources that address how to talk about suicide, deal with its aftermath, and prevent it from happening.

- National Officer Safety and Wellness (OSW) Group – Created by the Bureau of Justice Assistance and the Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, the OSW works to improve wellness and safety for law enforcement officers, share information, and address gunfire fatalities.Suicide Prevention Lifeline – Calling 800a273a8255 at any time of the day or night connects people with suicide prevention and crisis management resources.

Sources

Medical disclaimer:

Sunshine Behavioral Health strives to help people who are facing substance abuse, addiction, mental health disorders, or a combination of these conditions. It does this by providing compassionate care and evidence-based content that addresses health, treatment, and recovery.

Licensed medical professionals review material we publish on our site. The material is not a substitute for qualified medical diagnoses, treatment, or advice. It should not be used to replace the suggestions of your personal physician or other health care professionals.