Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental health condition that develops after a distressing event. It can stem from any number of things: combat, assault, abuse, accidents, natural disasters, terrorist attack, or learning about the violent or accidental death of a loved one something some refer to as dabda grief.

It doesn’t matter if the individual experiences the event or witnesses it.

It can manifest as flashbacks, avoidance, a more pessimistic outlook, and/or feeling on edge. That can be normal after a traumatic experience, and most people get better in time. Sometimes it takes a bit of self-care.

A person may have PTSD, however, if the symptoms:

- Continue for more than a few months.

- Are highly upsetting.

- Disrupt day-to-day life.

In such situations, treatment may prove very helpful.

Symptoms can start within a few weeks of a traumatic occurrence, but they can also be triggered many years after the event.

Symptoms of PTSD

PTSD symptoms will vary from person to person, but they are mostly grouped into four types:

- Reliving the event: This includes recurring and unwelcome memories, flashbacks, nightmares, and strong emotional and physical reactions to triggers.

- Avoidance: Here, a person may try to keep busy so they don’t have to talk or think about the event. They may also avoid people, places, and situations that remind them of the event. (Not wanting to think or talk about the trauma can be a symptom too.)

- Negative thoughts and feelings increase: A person may feel pessimistic or hopeless about the future; experience guilt or shame; have memory problems; feel distant from friends and family; lose interest in once-loved activities; and feel numb emotionally.

- Feeling keyed up or hyperaroused: Here, a person may startle more easily; be hyperalert for danger; engage in self-destructive behavior (drinking, drugs, speeding); have sleep troubles; struggle to focus.

Trauma can manifest in physical ways, too. The stress associated with it can contribute to anxiety, headaches, high blood pressure, heart disease, muscle pain, fatigue, and gastrointestinal issues.

Diagnosing PTSD

Mental health professionals should diagnose PTSD, but if symptoms last more than a few months, are deeply unsettling, and interfere with day-to-day life, that’s a sign that treatment may be necessary.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, aka the DSM-5, is the go-to book for mental health professionals to diagnose mental illness and disorders. The DSM-5 asks if you’ve been in or experienced:

- A serious accident or fire?

- Physical or sexual assault or abuse?

- A natural disaster (flood, tornado)?

- War or combat?

- Seeing someone killed or seriously hurt?

- A loved one die via suicide or homicide?

A yes answer to any of the above brings on a second set of questions, including:

Have you

- Had nightmares or unwelcome thoughts about the event?

- Tried not to think about the event, or did things to avoid reminders or distract yourself?

- Startled easily or been hypervigilant?

- Felt numb or detached from people, activities, or surroundings?

- Felt guilty or could not stop blaming yourself or others for what happened?

Answering yes to three or more of the questions doesn’t mean you have PTSD, but you may. It’s best to consult with a mental health provider to be sure.

Answering yes to one or two questions but experiencing symptoms that disrupt your life could mean treatment may be helpful. That combination of avoidance, re-experiencing events, hyperarousal, and mood symptoms strongly point to a PTSD diagnosis.

Causes of PTSD

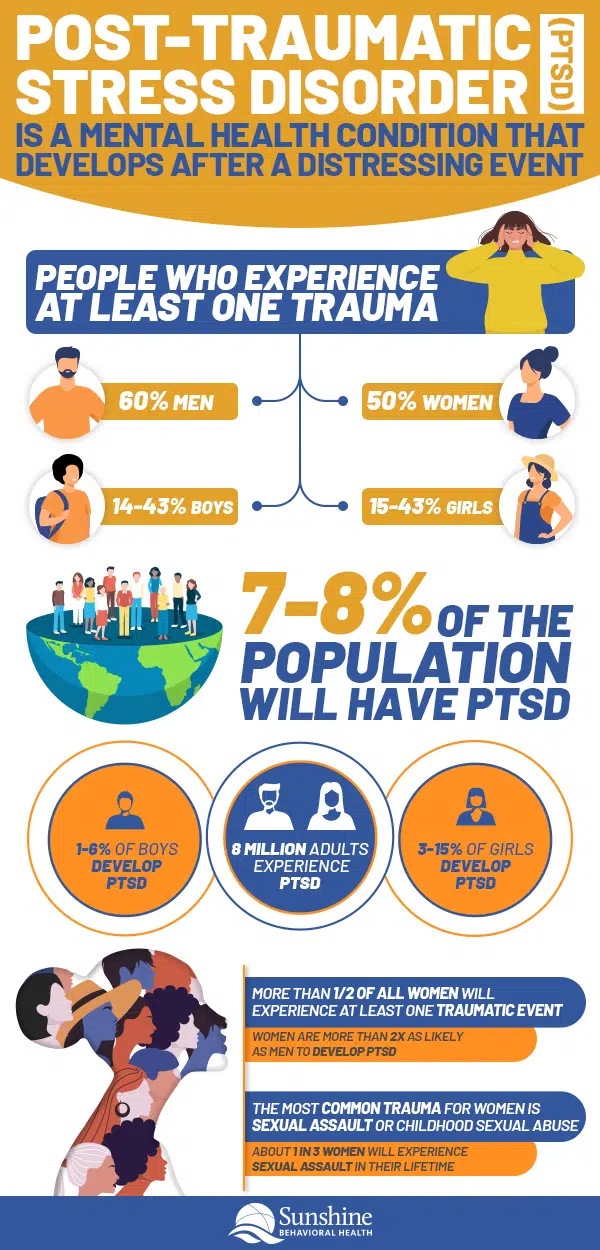

The National Center for PTSD estimates that 7-8% of people will experience PTSD at some time in their lives.

Just like with many mental health conditions, the exact causes of PTSD are complex, however. Some factors can make PTSD more likely, including:

- Trauma or abuse early in life

- Intense or long-term trauma, or coping with extra stress after an event such as a loss or injury. Even a natural disaster (including severe weather) can result in PTSD.

- Witnessing trauma (such as seeing someone get hurt or seeing a dead body)

- A job (first responders, military) that can expose people to regular trauma

- Mental health problems such as anxiety or depression

- Substance use disorder and substance use disorders

- A poor social support system

- Blood relatives with mental health issues

PTSD can raise the likelihood of many other problems. A traumatic event can spark changes in how the brain functions. Common symptoms include nightmares, anger, irritability, invasive memories, avoidance, panic, hypervigilance, a racing heart, headaches, and stomach pain.

Over time, it can result in disordered eating (obesity), poor school or work performance, drug and alcohol abuse, and mental disorders.

Some groups can be more vulnerable to PTSD. They include children and teens, military veterans, and victims of sexual trauma or racial and cultural discrimination.

PTSD in Children

Besides stemming from something such as an accident or disaster, a child or teen may develop trauma due to abuse (sexual, physical, or emotional), or neglect.

It’s worth noting that sometimes children’s PTSD may be mistaken for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) because of overlapping symptoms such as agitation, disruptive behavior, or inattentiveness. Both trauma and ADHD often co-occur with other conditions such as anxiety or depression.

Children may express trauma in various ways, at various ages.

Infants and toddlers may backslide on developmental milestones such as toilet training or speaking.

Very young children (six and younger) may re-enact some or all of the trauma through play. They also may have nightmares.

Very young children may also become unusually clingy, particularly with parents or caregivers.

A teen may act aggressively or engage in reckless or impulsive behaviors, possibly feeling guilty, believing they should have or could have done more. They may also ponder revenge.

PTSD in Veterans

People enlisted in the military may see combat or go on missions that expose them to devastating or dangerous experiences. That can result in PTSD.

Among Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom, Gulf War, and Vietnam veterans, between 11-20% have PTSD in any given year.

The politics surrounding the war, where it is fought, the type of enemy faced, and the things a soldier does in combat can lead to PTSD. So can sexual harassment or sexual trauma, which happens to both men in women, during peacetime, training, or war.

Rape or Sexual Trauma

Sexual violence is a broad term that covers all kinds of crimes. Legal definitions vary from state to state, but it can take on many forms, including:

- Sexual assault (rape and attempted rape, unwanted sexual touching, forced sexual acts)

- Intimate partner violence (also known as domestic violence)

- Child sexual abuse (exhibitionism, fondling, sex of any kind with a minor, child pornography, trafficking)

- Incest, or sexual contact between family

- Sexual assault of men and boys (who may feel shame for not being “strong enough” to stop the assault)

- Drug-facilitated sexual assault, when alcohol or drugs are used to make it easier to commit a sexual crime

Racial Trauma

Racial trauma stems from mental or emotional harm brought on by discrimination, racism, and hate crimes. Race-based discrimination can occur:

- Individually: Examples include the physical and verbal attacks leveled against many Asians and Asian-Americans during the COVID-19 pandemic, or a person with an accent being told to “go back to their country” is another example.

- Systemically: Examples include Black people making up 12% of the U.S. population but making up about one-third of the prison population, due to arrest, policing, and sentencing policies. In many cases, minorities (even if they have the same level of education, income, location, marital status, and age) are less likely to own homes, have jobs with benefits, or have access to mental health resources.

Both kinds of racism can lead to symptoms very similar to PTSD.

Learn About PTSD Treatment

Sometimes PTSD symptoms fade away in time, but for those whose symptoms persevere, there are effective PTSD treatments available. They mostly include talk therapies and/or medications.

First the medical professional will get the client’s history and note their symptoms. Then a treatment plan will be shaped. Some common psychotherapies include:

- Trauma-focused cognitive processing therapy (CPT) is a type of cognitive behavioral therapy. CPT focuses on the memory of the event or what it means. Most clients meet with a therapist once or twice a week. The goal is to reduce negative emotions (such as shame) and behaviors that follow trauma (and present obstacles) and learn healthier coping skills. The treatment may go on for three or four months. If the symptoms haven’t improved or gone away, then it may be time to consider alternative approaches.

- Prolonged exposure therapy (PE). Many people with PTSD try to avoid anything that reminds them of the trauma. It’s a temporary escape, but little else. PE exposes the client to whatever it is — a situation, location, thought, feeling — in a safe way so they learn that the trigger is actually harmless.

- Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR). PTSD sufferers have negative reactions to memories tied to the trauma. In EMDR the client focuses on specific sounds or movements (such as watching a light) as they talk about the trauma. That outside stimulus serves as a distraction, making it easier to process the memory. As the memory becomes less unsettling, the focus begins to add positive thoughts. For example, a person might come to view a violent attack with a more empowered mindset: “I was strong enough to survive.”

Medication can be effective too. That’s because people with PTSD may lack certain neurotransmitters that help them manage stress.

Antidepressants, specifically, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as sertraline or fluoxetine, or selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), such as venlafaxine, can be very helpful treatments. Medication only can help symptoms but not the cause, so therapy is still considered the more effective and lasting tool.

Some doctors may prescribe benzodiazepines (Xanax, Valium) to treat anxiety or insomnia. They can help at first, but because they can be addictive (and difficult to quit), they’re not considered the best course of treatment for PTSD.

PTSD Self-Help

Support groups can be very helpful for people with PTSD, not so much as a treatment but as a complement to therapy, or, following treatment, as a way to keep the focus on recovery. Other benefits include a sense of community, a judgment-free zone, a sense of empowerment, practical feedback, and learning opportunities.

Self-care can be beneficial, too. Exercise, for example, can help boost overall health and reduce stress. Mindfulness (yoga, meditation) can help when struggling with unpleasant emotions or troubling thoughts.

Setting realistic goals is good too. Focus on what you can handle. If need be, break tasks into smaller chunks.

Understanding that symptoms will not immediately fade away can also prove helpful.

A support animal, especially dogs (so long as you like animals), can bring out better feelings, serve as good companions, be a good distraction, take orders when trained, reduce stress, and provide an opportunity to go out and interact with others.

Support Your Loved One

When a family member has PTSD, it can affect the entire family as well as friends and other loved ones.

The person may grow distant, anger easily, or resort to alcohol or substance use.

A bystander may feel afraid, angry, or frustrated about these changes. You may not be able to provide a cure, but you may be able to provide support in various ways. Tips include:

- School yourself on PTSD. The more you know, the easier it can be to understand the loved one’s struggles.

- Offer to accompany your loved one to doctors or other treatments.

- Tell them you want to listen, but if they aren’t ready to talk, that’s also fine.

- Include them in family activities. Engage in physical activity together. It can serve as a healthy distraction and it’s good for overall health.

- Encourage keeping in touch. Knowing they have someone to talk to can help during stressful times.

- If the loved one has angry outbursts, set up a time-out system so everyone can take a break and keep things from escalating. If things do get out of hand, call for help right away.

Find Information and Resources

Support is available for both the person with PTSD and loved ones. No one should have to suffer it alone.

If you’re in crisis, consider:

- National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. suicidepreventionlifeline.org. 800a273a8255 (TALK)

For veterans:

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). Visit va.gov/directory/guide/PTSD.asp for a local PTSD program. To find your local VA medical center, click here.

- Veterans Crisis Line. If you feel suicidal, call 800a273a8255, then PRESS 1 or visit the Veterans Crisis Line online.

- Peer Support at Vet Centers. To speak with other veterans, call 877a927a8387 or go online to find a center near you.

- Make the Connection. Information, resources, and veteran-to-veteran videos for challenging life events and experiences with mental health issues.

- RallyPoint. A social network for veterans.

- VA’s self-help apps. Veterans can download tools to help deal with common reactions such as stress, sadness, and anxiety. They can also track their symptoms over time.

PTSD overall:

- PTSD Coach Online. A series of videos to help manage stress. For trauma survivors, family members, or anyone coping with stress.

- SAMHSA (Substance Use Disorder and Mental Health Services Administration). This federal clearinghouse of information has a behavioral health treatment services locator where people narrow their search via specific criteria (such as zip code or if one is in the VA). SAMHSA also has a National Helpline, 800a662aHELP (4357) for anyone facing mental or substance use disorders.

- National Alliance on Mental Illness. 800a950a6264 (NAMI) or text “NAMI” to 741741. This site has information and resources for anyone facing mental health challenges as well as information for specific groups (Asian American and Pacific Islander, Black/African American, Indigenous, Hispanic/Latinx, LGBTQIA, and People with Disabilities). Resources are also available for teens and young adults, family members and caregivers, veterans and active-duty personnel, and frontline professionals.

- RAINN (Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network). 800a656a4673 (HOPE). For survivors of sexual assault.

- Disaster Distress Helpline. SAMHSA’s helpline provides crisis counseling and support around the clock to people in distress over natural or human-created disasters. Call or text 800a985a5990.

Sources

Medical disclaimer:

Sunshine Behavioral Health strives to help people who are facing substance abuse, addiction, mental health disorders, or a combination of these conditions. It does this by providing compassionate care and evidence-based content that addresses health, treatment, and recovery.

Licensed medical professionals review material we publish on our site. The material is not a substitute for qualified medical diagnoses, treatment, or advice. It should not be used to replace the suggestions of your personal physician or other health care professionals.